Record numbers of towns, in all parts of the state of Vermont, have rejected school budgets this year in protest over ever rising property tax rates and education costs spiraling out of control. In St. Johnsbury, the town where I work, residents recently voted down their school budget for the third time.

Those who support the increased school budget often attempt to characterize their opponents as people who hate children or do not care about the future of the town. Comments such as ” It’s a sad day for our children who are not worth this town’s investment.” and “These are people [staff and teachers] who care deeply about the kids and are now being shown that the townspeople of St. Johnsbury do not care.” are representative not only of the feelings of supporters after the failed vote but also of the arguments they made leading up to the it.

Arguments such as these appeal to one’s emotions and present a false alternative. These are two common logical fallacies and as such should be dismissed. They ignore the fact that most people do care deeply about both the children and the town, but they are also aware that property taxes, or any taxes for that matter, simply cannot be increased endlessly, not for education nor any other purpose.

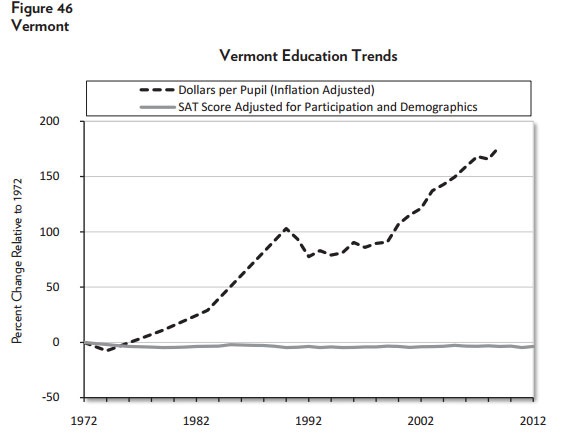

The school board, and their supporters, simply failed to make a good case that the increased spending would, in and of itself, lead to better outcomes for the students. Before the initial Town Meeting Day vote, I did not see any claims that higher spending equals better educational outcomes. This is not surprising as the trends in American education over the 40 years since the establishment of the Department of Education would invalidate any such claims. In that time, the per pupil spending in public schools, adjusted for inflation, has nearly tripled while the academic performance has remained unchanged or declined. Vermont is not materially different from the national trend, as the graph below shows.

Instead, the arguments made by the superintendent of schools were more of the “keeping up with the Joneses” variety. The first argument I saw in the Caledonian-Record was that the town should increase spending because other area towns spent more per student than St. Johnsbury did. There was no evidence given that these schools had better outcomes, let alone that the higher spending was the cause for these outcomes. While it is certainly possible that the arguments may have been mischaracterized, a letter to the editor by the superintendent herself repeated, in essentials, this same argument, this time stated as the idea that St. Johnsbury could afford to raise taxes as it had lower tax rates than other towns.

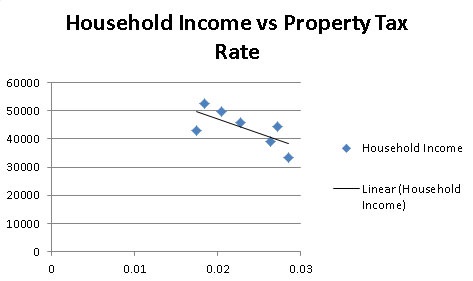

She then doubled down with the idea that raising taxes and increasing spending would be a form of economic stimulus. This notion is something that seems unlikely on its face, but I did not have anything other than my common sense to go on. That is, until a few weeks ago when I came across an insert to a local paper that gave the property tax rates and median household incomes for all the towns in the Northeast Kingdom, the area where St. Johnsbury is located. My curiosity aroused, I entered all this data into a spreadsheet in order to see just what the relationship is between these two values. Median household income is not a perfect measure for the economy of a town, but it is not implausible to use it, as a stimulated economy should result in more money per household. The graph below summarizes the data for all towns of somewhat comparable size, more than 2000 residents. (St. Johnsbury has 7603 according to the data I have.)

The trend is pretty clear: As property tax rates increase, the median household income declines. While this correlation cannot prove that the higher tax rates cause the lower median incomes, it certainly indicates that raising taxes will not result in the higher median incomes, which one would reasonably expect if the economy was being stimulated. (The full set of data for all 49 towns, populations ranging from 62 to 7603, has a trend line that is essentially flat.)

Tinkering at the margins by trimming this program here and cutting $45,000 there, as St. Johnsbury has attempted to do to gain voter approval for their budget, does nothing to address the underlying causes of both rapidly increasing costs and stagnant performance. Nor does characterizing opponents to the increased spending as heartless monsters who care nothing for the children. If we are meant to seriously question whether someone cares for the children, we should ask ourselves who cares more – those who want to put more money into an immoral, coercive system which has failed to produce better outcomes despite massive increases in spending, or those who understand that the system is broken and cannot continue on its present course, even if they cannot clearly articulate, or perhaps even conceive, what the real problem is or its solution.

What is needed in education, not just in St. Johnsbury but state and nation wide, is a fundamental revolution in the entire system. This must include an eventual, complete separation of government and education. Such freedom in education would inevitably lead to much improved performance and reduced costs. (According to a recent study, costs at private schools today are about 34% less than in public schools and have better outcomes. This margin would likely increase without the government’s current monopoly on education.) You need only look at the tech industry to get a glimpse of what might be possible without government interference. Just as the relative freedom in technology has given us telephones we can carry in our pockets that have more computing power than the mainframe computers of 40 years ago, I have no doubt that similar freedom in education would lead to the same level of amazing results.

If you really care about the children, this is what you should be advocating for.

Look for Ms. Bledsoe, et al to start flooding the newspaper with editorials and letters to the editor bemoaning the drastic consequences that will be “unavoidable consequences of the refusal to sufficiently fund our children’s education”. Namely, they will say it’s necessary to cut extracurricular activities such as sports, music, art, etc.

They’ll wring their hands very publicly about how terrible it is that “our kids” will have to “pay the price” without even once considering the possibility of eliminating some of the unnecessary administrative costs (admin has increased every year, even as student enrollment numbers have gone down), getting rid of so-called “para-educators” (there’s no reason why those positions couldn’t be handled by upperclassmen, same as in the past) and getting rid of their addiction to small class size and requiring teachers to handle a class of 30, as opposed to a class of 20 or less. Of course, such common sense solutions are anathema to the union-controlled teaching profession.

I particularly liked how Ms. Bledsoe commented how she “couldn’t understand” why the budget failed, remarking that people must just “not understand” school funding. Yeah, the tax payers are too ignorant to make the proper choices, that’s it.

Speaking of extracurricular activities, the issue there is the fact that they are EXTRAcurricular, meaning outside the regular curriculum or program of courses. More and more these activities, which do have value, are being given priority ahead of the actual curriculum. When sports, for example, receive the same emphasis as, or in some cases greater emphasis than, subjects such as science or mathematics, it is no wonder that there has been no improvement in test scores.

I am sure your prediction is spot on that there will be a flood of letters to the editor bemoaning how the opponents of the budget “hate children.” The comments I included in the post were from taken from the comments on the Caledonian’s Facebook post of the news. Those supporting the budget will insist that this must be done, for the children, while refusing to see that, if history is any guide, increased spending will simply impoverish the present to no benefit for the future. In other words, it will sacrifice, properly understood as giving up a value for a lesser or non-value, the present to some vague promise of a better future.

Just came across this at The Objective Standard and it seems to fit with this post.